Gender Dynamics by Steve Spotswood

To say I am sensitized to gender dynamics in my plays might be an understatement.

I’m not sure when it started. It might have been grad school; it might have been earlier.

The first full-length play I wrote after entering grad school centered on two middle-aged women who had been each other’s first loves when they were teenagers and who were rediscovering each other decades later under difficult circumstances. One had grown up to become an anthropologist, the other the minister of their hometown. One was out and married to another woman; the other ostensibly closeted.

On one hand, I was developing a deeply emotional and physical relationship between two teen girls. On the other, I was navigating a messy intersection of faith, grief, trauma, and sexuality.

And then, of course, there was the child abuse.

I don’t remember who said it, my professor or one of the other students in the writing seminar. But it went something like: “This is going to make somebody mad at you. There’s no getting around it.”

And as a twenty-eight year old heterosexual male writing about 40-something gay women, I totally believed it. So I made sure that I could back up every choice I made: from making the maybe-gay minister the most likable person in the play to opening Act Two with a sex scene between the two teens.

It helped to have a dramaturg wife (then fiancé) completing her MA in Theater History and Criticism with a focus on gender theory that I could bounce ideas off of. It also helped that the first director to work deeply with me on the play was a gay woman around my protagonist’s age who I was confident would call me on any bullshit.

In the bazillion readings and one college production of the play, no one has ever expressed their displeasure about the themes and gender dynamics of the play.

But I think it set a precedent for me of a) writing a lot of gay women and b) making sure I understood the gender dynamics of the stories I’m telling. Not to say that those dynamics are always nice and neat and balanced. But if they’re unbalanced, I like to have a good reason for it.

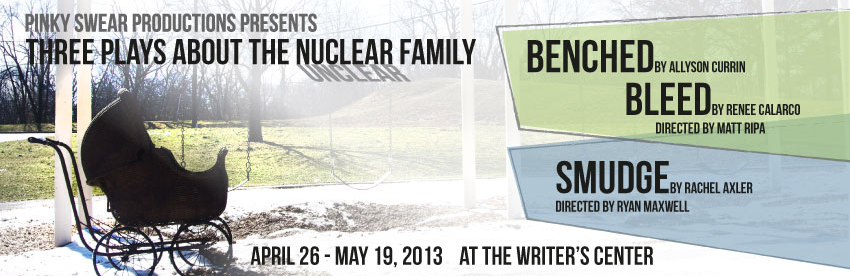

Which brings me to working with Pinky Swear Productions. I was first introduced to the company in 2011 with their Capital Fringe production CABARET XXX, a show so nice my wife and I saw it twice. After that, we made a point to see all their shows, from their irreverent take on a Christmas Carol (CAROL’S CHRISTMAS) to the surprisingly funny story about murderesses for hire (KILLING WOMEN).

Their mission is to produce theatre that highlights strong roles for women, as well as provide more opportunities for female theatre artists of all types.

By the time summer 2012 rolled around, the company and I knew each other a little better. And I was thinking, “Hey, they make theatre for women. I write a lot for women. We should really do something together.”

And so I pitched an idea for a play that I could write and workshop with Pinky Swear that, if all the stars aligned, they might produce in the near(ish) future.

They thought it was a good idea, too. And when Pinky Swear created its Associate Artist program this past fall, inviting a handful of local artists to work with them, I joined up. So, not only do I get to write a play for them, but I’ve got a whole slew of actors and other artists to draw inspiration (and potential collaborators) from.

There’s a certain kind of joy that comes from creating a bespoke piece of theatre — something tailored to the make-up and aesthetic of a particular group of artists.

And there’s a certain amount of pressure.

The play I pitched is tentatively titled THE LAST BURLESQUE and takes place during the final weeks of a failing burlesque/sideshow house. Right now I’m describing it as a love story between a suspension burlesque artist and the daughter of a dead clown.

The plot is still unfolding (I’m somewhere in the murky middle), but however it plays out there’s going to be burlesque. Maybe a lot of it.

(Also magic, contortionists, human blockheads and, if the permits come through, fire eating.)

I like burlesque for two reasons. a) It’s sexy (duh) and bold and the form encourages creativity and b) It’s all about delaying the reveal. You keep the audience on the edge of suspense for as long as you possibly can. Which can be one of the keys to good drama.

Already several burlesque/sideshow themes are emerging: the nature of exhibitionism; the comodification of the Other (or, as one character puts it, “the gentrification of the weird); the human body as art; the audience as voyeur.

Which is all well and good. But if all the stars align and Pinky Swear produces this piece, it’s not going to be the metaphors that are twirling tassels on stage.

I’ll be asking actresses (and very possibly at least one actor) to perform burlesque routines start-to-finish onstage. And it’s quite likely that I know who those actors and actresses are going to be. They’re the people in the room reading installments of the first draft as I bring them in.

Which really feels like it ups the whole understanding-gender-dynamics stakes.

But maybe it doesn’t. Maybe this is me overthinking. The core company members knew the subject matter of the play going in, and they signed on anyway, trusting me not to throw in a bushel of tits and cock and ass just for the sake of tits and cock and ass.

Which is not to say that sometimes theatre can’t use a little tits/cock/ass for the sake of it. See? Balance. Hard.

And it’s not like the members of Pinky Swear are naïve about the gender politics of theatre (They’re so not naïve, I’m laughing while I write this sentence). They will call me on my bullshit. Or at least ask firm questions about what the fuck is going on in a scene.

But because they are so smart about gender and theatre, and because that’s a core reason the company came about, that makes me want to not fuck up even more.

This isn’t to say that I’m pulling punches. As soon as I’m done with this post, I’m finishing a chunk of dialogue where a character describes in erotically-charged detail the sensation of hooks being pierced through her shoulders and back.

Let’s just that when I swing, I’m doing my best to know what I’m aiming for.

e now basking in the glow of our first full season of programming. It is a good time to be us.

e now basking in the glow of our first full season of programming. It is a good time to be us.